We use Jsonnet extensively at Databricks.

There are various pre-existing editor tools and plugins for Jsonnet, like Jsonnet LSP by Carl Verge and Jsonnet Language Server by Grafana. But I wanted to try making my own.

So I created rjsonnet, a Jsonnet language server in Rust. It is available as a VS Code extension.

Screenshots

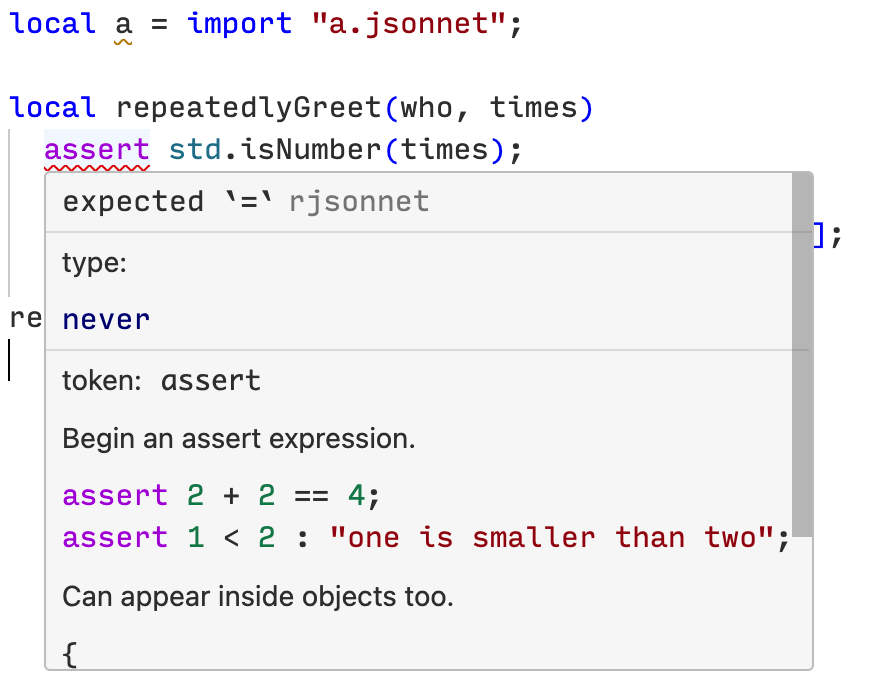

Syntax highlighting, error tolerant parsing, and inline diagnostics

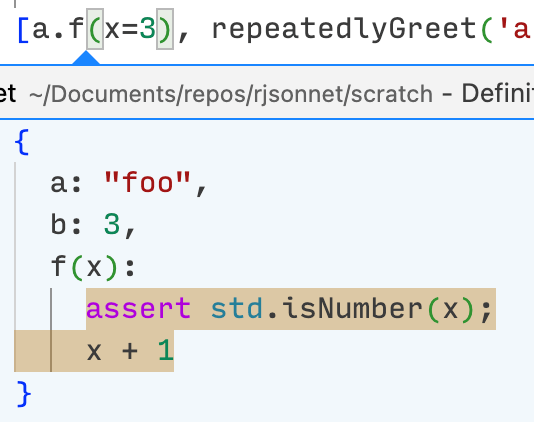

Go to (or peek) definition

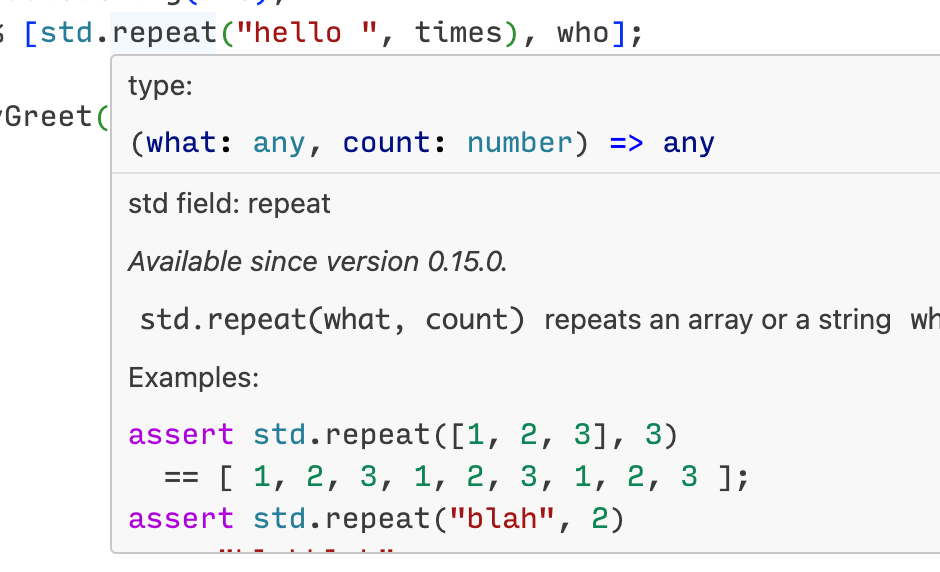

Hover for type, standard library docs, and typechecking

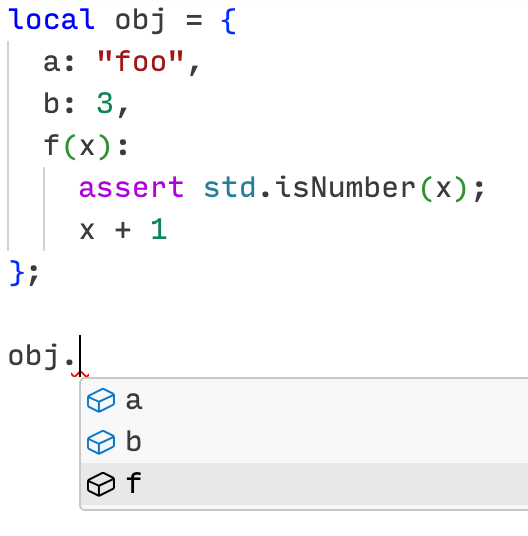

Auto-complete object fields

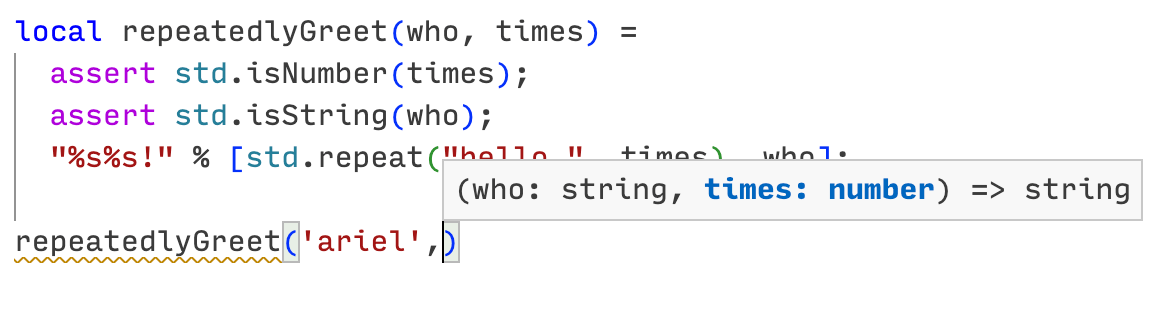

Type annotations and signature help

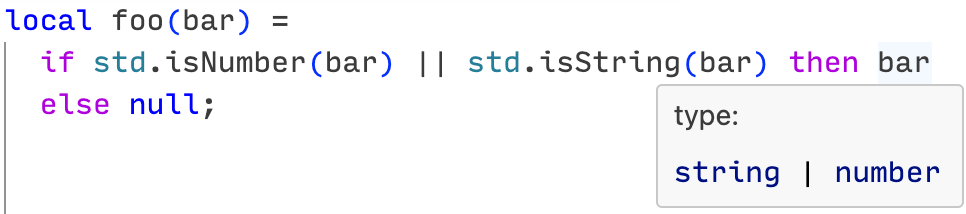

Flow typing

Features

As shown above, its has a lot of the usual features you’d expect from a language server:

- Syntax highlighting

- Error tolerant parsing

- Inline errors and warnings

- Go-to-definition

- Standard library documentation

- Hover for info

- Auto-completions, via knowing what fields are on an object

- Signature help, when calling a function

Although Jsonnet does not have static types or type annotations, the language server does perform type inference. This powers some advanced features like auto-completions.

There is also a way to add simple “type annotations” to function parameters, without changing the syntax of Jsonnet. You add type assertions on the parameters to the beginning of your function, like this:

local repeatedlyGreet(who, times) =

assert std.isNumber(times);

assert std.isString(who);

"%s%s!" % [std.repeat("hello ", times), who];

This will be inferred to have type:

(who: string, times: number) => string

Design

The implementation is generally broken up into a few distinct stages, which proceed one after the other.

It is important for any language server to be able to analyze code as the user is in the middle of writing it. Because of this, each stage is designed to work with syntactically malformed input and still always produce some partial output, instead of just erroring out and giving up.

Lexing

The lexer, aka tokenizer, turns a file from a sequence of bytes into a sequence of tokens.

Tokenizing always produces a sequence of tokens which can be reassembled in order to reproduce the original file, byte-for-byte identical. To allow this, we have:

- An “error” token which represents invalid Jsonnet.

- Comment and whitespace tokens, collectively called “trivia”, that are ignored during parsing.

Parsing

The parser is also error tolerant. It parses files into an untyped concrete syntax tree. As in lexing, a file can be reproduced byte-for-byte identically from the concrete syntax tree.

Desugaring

The concrete syntax tree is wrapped in a typed abstract syntax tree API so that it may then be lowered into a simpler representation, the “HIR”, or high level intermediate representation.

During this transformation, certain constructs are rewritten in terms of other, more fundamental ones. Some examples:

| Complex | Simple |

|---|---|

a && b |

if a then b else false |

a != b |

!(a == b) |

local f(x) = e |

local f = function(x) e |

assert a : msg; b |

if a then b else error msg |

The HIR is represented approximately like this:

enum Expr {

Bool(bool),

Number(f64),

If(ExprIdx, ExprIdx, ExprIdx),

Fn(Vec<Param>, ExprIdx),

...

}

type ExprIdx = Option<u32>;

type ExprArena = Vec<Expr>;

We have a main enum representing all possible “expressions” (Exprs). There is an enum case for each different kind of expression, like literals, if, function, local, assert, array comprehensions, etc.

We also have an arena which is basically just a Vec of all the Expr enum we generate when desugaring the AST into HIR.

When expressions are recursive (i.e. contain sub-expressions), we use ExprIdx, which is either an index into the arena of expressions or None.

The index is optional because we must permit representing partially-formed documents. For instance, if we’re in the middle of refactoring an if expression and we have:

local func(x) =

if then 3 else x + 1

// ^ cursor here, just deleted the condition

We would represent that by having None for the conditional expression of the if.

Using an arena instead of allocating sub-expressions ad-hoc (e.g. with Box or Rc) improves cache locality and reduces memory fragmentation. As an added bonus, it also lets us use the expression indices as cheap IDs, e.g. when reporting what expression an error occurred on.

Static analysis

We do static analysis on the files. This checks things like whether variables are in scope.

We also check the types of expressions, to some degree. We carry out a limited form of type inference; we do not infer constraints on function parameters as is done in a Damas-Hindley-Milner type system like Haskell’s or Standard ML’s. Instead, function parameters are assumed to be of any type, but can be “annotated” with type assertions at the beginning of the function.

To check the types of expressions, we need to know the types of imported files. This means there is a dependency order between the files, and we must do static analysis of “leaf” files first before later files. This is unlike the previous stages, in which each file could be analyzed (almost) completely independently.

Performance

In addition to tolerating error states, a language server should be performant. It should quickly respond to user edits and still provide useful, up-to-date information, while using low CPU and memory.

Performance is a feature. The goal of high performance drove many key design decisions in the implementation.

Interning

For important types whose values may be repeated multiple times during program analysis, we use a technique called “interning”, where we store the unique values a constant number of times instead of re-allocating for each instance.

For instance, even if the same string occurs many times in the program text, we don’t repeatedly allocate that same string each time. Instead we store that string in the string arena and hand out cheap integer-sized indices into the arena.

We also intern the values that represent the static types we encountered in the program. If multiple parts of the program are both inferred to have the same type, there will a shared allocation for the value representing that type.

Parallelizing, combining, and substituting

We noted before that the early stages of analysis - lexing, parsing, and desugaring - on a given file are independent from other files.

This was a bit of a fib. It’s true for lexing and parsing, but not for desugaring.

When we desugar, we carry out string interning. This requires us to mutate the string arena to add new strings as we encounter them. This is problematic, since now we have mutable state that we want to share across parallel tasks.

Once way we could resolve this is putting the single global mutable string arena behind a synchronization primitive like a mutex or read-write lock. Given that this string arena will likely experience high contention during desugaring, this would probably lead to poor performance.

Another choice, which is what we do, is to desugar in parallel with no shared mutable string arena, and instead produce a separate arena from each desugaring. This means there is no need for synchronization primitives and thus no contention.

But now we have a separate string arena for each file. This means we could have the same string that gets interned at different indices across different desugars.

For example, consider these two files:

["foo", "bar"]

["bar", "foo"]

Desugaring basically processes the file in the same order as the source text. So we’ll intern “foo” first in the first file and “bar” first in the second. We’ll then end up assigning the same interning indices to different strings in the two files.

To make later stages of analysis more convenient, we’d like to combine the different per-file string arenas into one, instead of having to carry around the per-file string arena for each file.

But when we combine one file’s string arena with the global one, the same string may end up at a different index, as shown in the above example.

So when combining, we need to also produce a substitution from old string indices to new ones, that we then apply to the desugared file.

This general idea, of:

- generating individual arenas to avoid contention,

- then combining the arenas, which generates a substitution,

- that we then apply to affected values which contain indices into the arenas

is a technique I learned from Dmitry Petrashko from his work on Sorbet, a type-checker for Ruby built at Stripe, where I interned twice and worked full-time for 3 years.

Topological sorting and per-level parallelization

We also use this technique in static analysis, since we store types in arenas as well. However, for static analysis, there are even more data dependencies between files, because we must type-check imported files before the importing files.

To make sure we analyze files in the right dependency order, we perform a topological sort of the files based on their imports, and parallelize for each the “levels” in this sort.

For instance, consider we’re analyzing a file named A that imports files B and C, which then import other files. We can visualize the graph of dependencies by laying out nested dependencies further down and the root node A at the top, with an arrow denoting depends on . Our example graph looks like this, with each level number also noted:

Which is also given by this table:

| File | Imports | Level |

|---|---|---|

| A | B, C | 0 |

| B | D, E | 1 |

| C | E, F | 1 |

| D | None | 2 |

| E | G, H | 2 |

| F | None | 2 |

| G | None | 3 |

| H | None | 3 |

We then analyze each level, starting from the furthest down and working up. Files on a given level can be analyzed in parallel, since they do not depend on each other. And we start at the furthest level down and go up, so that dependencies are analyzed before the dependents.

In this example, we would analyze:

- G, H

- D, E, F

- B, C

- A

Caching

We cache results of files between updates so that if the file doesn’t change, we don’t recompute its parse tree, static analysis information, etc.

Delta updates

When a file updates, the language client (e.g. VSCode) is configured to send only the text of the file that updated, instead of the whole file.