Many programming languages have both terms and types. Terms are also sometimes called expressions.

- Terms, like

3orfalse, denote the data being manipulated. - Types, like

u32(aka “unsigned 32-bit integer”) orbool, describe what operations are permitted on terms.

For instance, if we have a term of type u32, we might be able to do things like add or subtract with other u32s. And if we have a term of type bool (aka true or false), we could do things like negate it or use it to branch with an if construct.

Many programming languages also have functions. For example, we could define the function is_zero, which takes a term of type u32 (like 3) and returns a term of type bool (like false).

is_zero is a function from terms to terms. However, given the existence of both types and terms, there are distinct varieties of function to consider:

- From terms to terms

- From types to terms

- From types to types

- From terms to types

Let us examine some examples of each kind of function.

Terms to terms

As mentioned, the most common kind of function is the one that takes a term and returns a term, like is_zero.

For example, in Rust:

fn is_zero(n: u32) -> bool {

n == 0

}

Types to terms

Consider the identity function, which is the function that returns its argument unchanged.

The implementation of the identity function is identical for any choice of parameter/return type: just return the term passed in. So, it would be convenient if, instead of having to define a “different” identity function for every type, we could have a single identity function that would work for any type. This is sometimes called a generic function.

What we can do is allow the identity function to take a type argument. Let us call it T. We then take a term argument whose type is T and return it.

In a sense, then, the identity “function” is actually defined with two functions. First is a function that takes a type T and then returns a term. That term is also a function. It takes a term x of type T, and then returns that term x.

In Rust, the identity function is:

fn identity<T>(x: T) -> T {

x

}

Types to types

Many programming languages provide a list type, which is a ordered sequence of elements that can be dynamically added to and removed from. Different programming languages call this type different things: list, array, vector, sequence, and so on, but the general idea is the same.

We would like a list type to permit the elements stored to be any fixed type. That is, instead of separately defining ListOfU32 and ListOfBool, we would like to just define List, and have it work for any element type. This is called a generic type.

But note that List itself is not a type. Rather, it is a function that takes a type (the type of the elements) and returns a type (the type of lists of that element type).

In Rust, the list type is called Vec. So, if T is a Rust type, then Vec<T> is the type of a vector of Ts.

We can combine type-to-term and type-to-type functions to write highly generic, reusable code. For instance, we could write a Rust function push that takes a vector and an element to add (“push”) to the end of the vector, then returns the new vector.

fn push<T>(xs: Vec<T>, x: T) -> Vec<T>

Note that:

- In

fn push<T>, theTis a type parameter. This is an example of a type-to-term function. - In

Vec<T>, theTis a type argument. It is being passed to the type-to-type functionVec.

Terms to types

Some languages have a fixed-length array type. This is a type which is a bit like a list, but its length is fixed, and thus part of the type itself. Languages like C and Rust permit types like this.

For instance, in Rust, the definition

const A: [u32; 3] = [2, 4, 6];

defines A to be an array, with a fixed length of 3, of 32-bit unsigned integers. Note that the term 3 appears in the type [u32; 3].

As we’ve seen, Rust allows type-to-term and type-to-type functions via generic type arguments. Rust also allows for term-to-type functions with a feature called const generics:

type U32Array<const N: usize> = [u32; N];

Here, U32Array is a function from a term to a type. The input term N has type usize, and the output type is the type of arrays of unsigned 32-bit integers with length N.

We can use it like this:

const A: U32Array<3> = [2, 4, 6];

Types like [u32; N] that contain, or “depend on”, terms, are called dependent types. Not many programming languages fully support dependent types, likely due to their incredible expressive power.

Notably, Rust only permits using term-to-type functions when the terms are known before the program actually runs (aka, const).

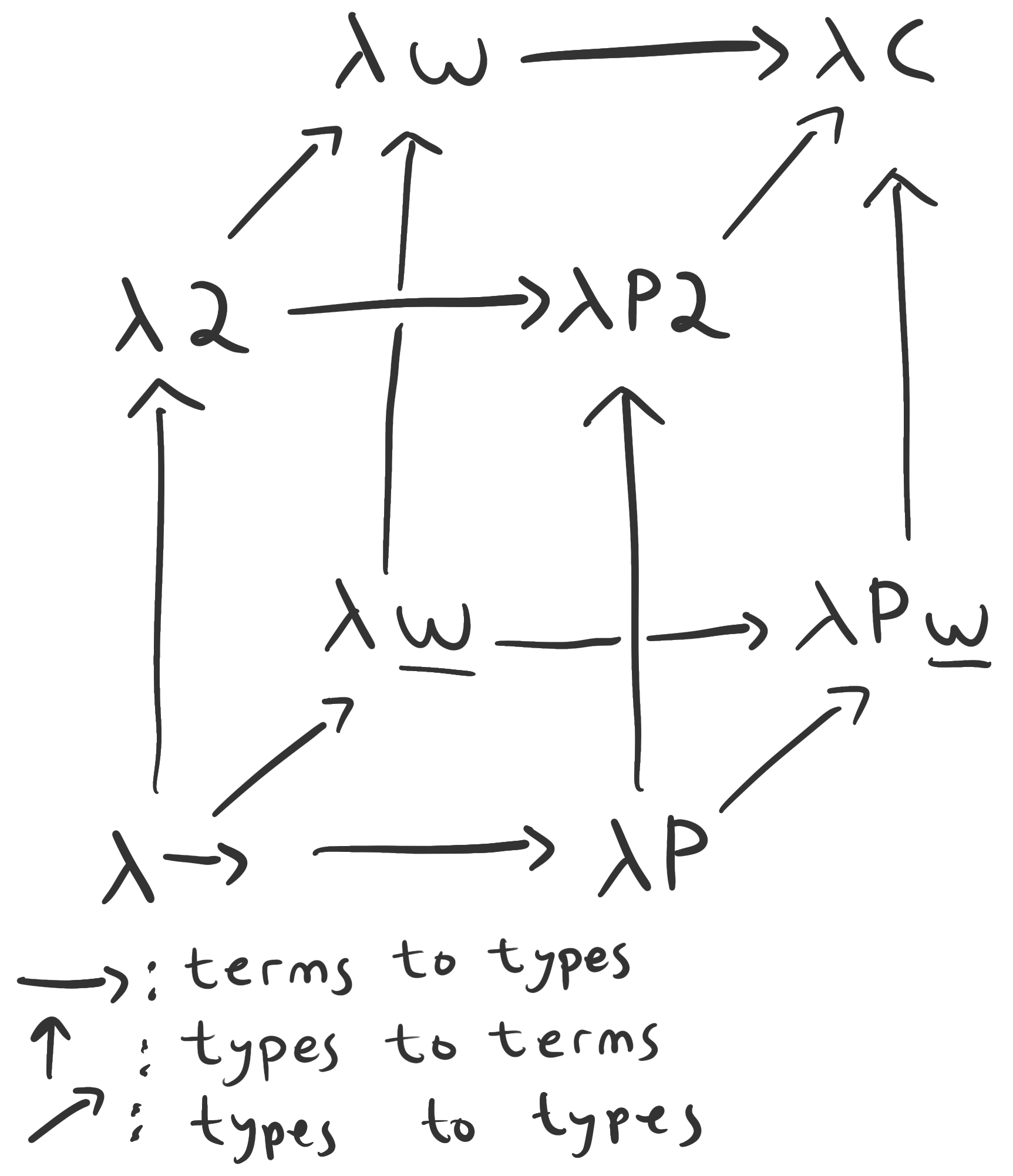

The lambda cube

To reiterate, the four varieties of functions are:

- From terms to terms

- From types to terms

- From types to types

- From terms to types

Most languages have term-term functions, but choose to allow or disallow the other three varieties of functions. There are three yes-or-no choices to make, and thus possible configurations.

We may visualize the three choices as dimensions, and thus organize the possibilities into a cube. The vertices of the cube represent languages that arise from choosing combinations of allowing or disallowing the three varieties of function. All vertices on the cube allow for term-to-term functions.

Some commonly-known vertices on the cube are shown below. Columns 1-4 correspond to the 4 varieties of function discussed.

| Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simply typed lambda calculus | ✓ | × | × | × | |

| System | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | |

| System | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × | |

| Calculus of constructions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Once we reach the calculus of constructions (CoC), the distinction between types and terms somewhat disappears, since each may freely appear in both themselves and the other. Indeed, as powerful as the CoC is, it has a very sparse syntax of terms, fully described by the following context-free grammar:

There is no separate syntax for types in the CoC: all terms and types are represented with just the above syntax.

I wrote up an implementation of the CoC in Rust for edification.

The calculus of constructions serves as the foundation for many dependently-typed programming languages, like Coq. Using the CoC as a foundation, Coq is able to express and prove mathematical theorems like the four-color theorem.

It’s rather remarkable to me that functions and variables, the most basic realization of the concept of “abstraction”, can be so powerful in allowing all different types of language features. In the words of jez, on variables:

I think variables are just so cool!

And functions:

I think it’s straight-up amazing that something so simple can at the same time be that powerful. Functions!